UCL Institute of Education

| |

Former names | UCL Institute of Education[2] Institute of Education, University of London London Day Training College |

|---|---|

| Established | 2014 – as a constituent faculty of University College London 1932 – as a constituent institution of the University of London 1902 – teacher training college |

| Endowment | £90.5 million |

| Chancellor | The Princess Royal (University of London) |

| Director | Li Wei |

| Location | London , United Kingdom |

| Campus | Urban |

| Website | ucl.ac.uk/ioe |

The UCL Institute of Education (IOE) is the faculty of education and society of University College London (UCL). It specialises in postgraduate study and research in the field of education and is one of UCL's 11 constituent faculties. Prior to merging with UCL in 2014, it was a constituent college of the University of London. The IOE is ranked first in the world for education[3] in the QS World University Rankings, and has been so every year since 2014.[4][5]

The IOE is the largest education research body in the United Kingdom, with over 700 research students in the doctoral school. It also has the largest portfolio of postgraduate programmes in education in the UK, with approximately 4,000 students taking Master's programmes, and a further 1,200 students on PGCE teacher-training courses. At any one time the IOE hosts over 100 research projects funded by Research Councils, government departments and other agencies.

History

[edit]

In 1900, a report on the training of teachers, produced by the Higher Education Sub-Committee of the Technical Education Board (TEB) of the London County Council, called for further provision for the training of teachers in London in universities.[6] The TEB submitted a scheme to the Senate of the University of London for a new day-training college, which would train teachers of both sexes when most existing courses were taught in single-sex colleges or departments. The principal of the proposed college was also to act as the Professor of the Theory, History and Practice of Education at the university.[6] The new college was opened on 6 October 1902 as the London Day Training College under the administration of the LCC.[6][7]

Its first principal was Sir John Adams, who had previously been the Professor of Education at University of Glasgow.[8] Adams was joined with a mistress and master of Method (later Vice-Principals).[6] The bulk of the teaching was carried out by the Vice-Principals and other specialists were appointed to teach specific subjects, including Cyril Burt.[6] Initially the LDTC only provided teacher training courses lasting between 1 and 3 years.[6]

The LDTC became a school of the University of London in 1909 and was wholly transferred to the university and was renamed the University of London, Institute of Education in 1932.[9] Gradually the institute expanded its activities and began to train secondary school teachers and offered higher degrees. It also moved into specific areas of research with its Child Development Department, administered by Susan Sutherland Isaacs and the training of teachers for the colonial service. At the outbreak of World War II, the institute was temporarily transferred to the University of Nottingham.

As a result of the report of the McNair Committee,[10] which was established by the Board of Education to examine recruitment and training of teachers and youth leaders a new scheme for teacher training was established in England.[11] "Area Training Organisations" (ATO) were created to co-ordinate the provision of teacher training and were responsible for the overall administration of all colleges of education within their area.[12] The ATO for the London area was based at the University of London under the name University of London, Institute of Education, which was responsible for around 30 existing colleges of education and education departments, including the existing Institute of Education. The colleges (known as "constituent colleges" of the institute) prepared students for the "Certificate in Education" of the institute, and latterly for the Bachelor of Education and Bachelor of Humanities degrees of the university. The existing institute (referred to as the "Central Institute") and the new ATO (referred to as the "Wider Institute") had separate identities, but confusingly were administered from the same building and by the same administrative staff. This dual identity continued until the Wider Institute gradually disappeared and was finally dissolved in 1975, coinciding with the closure (or "merger" with local polytechnics and other institutions) of many of the colleges of education.

In 1987 the institute once again became a school of the University of London and was incorporated by royal charter.

The IOE and UCL formed a strategic alliance in October 2012, including co-operation in teaching, research and the development of the London schools system.[13] In February 2014 the two institutions announced their intention to merge[14][15] and the merger was completed in December 2014.[16][17]

In March 2015 it was announced that the IOE would be the lead partner in the UK Centre for Global Higher Education, a new centre focusing on the systematic investigation of higher education and its future. The Economic and Social Research Council announced that it would provide £5 million in funding for the centre for the period to 2019, the other partners in which are Lancaster University and the University of Sheffield.[18]

Campus

[edit]

The first home of the IOE (as the London Day Training College) was Passmore Edwards Hall on Clare Market, which belonged to the London School of Economics. It moved again in its second year to the Northampton Technical Institute in Finsbury and the College of Preceptors building in Bloomsbury Square.[6] In 1907 the college moved to its first purpose-built building on Southampton Row.[6] In 1938, the institute moved to the Senate House complex of the University of London on Malet Street.[6] After World War II, the Senate House complex became unworkable due to a sharp increase in numbers of students. The institute began to expand into other buildings in the neighbouring area, including four houses on Bedford Way which were leased as a residential hall for students in 1946, a building on Tavistock Square as home of the music department in 1958, and a few "huts" on Malet Street (formerly belonging to the University of London Student Union) where the library was transferred.[6] In 1960, plans were prepared for a new building on Bedford Way designed by Denys Lasdun, though only part of his initial design was completed.[6] The library was one of the aspects dropped from the design and in 1968 it was moved from huts into a converted office block on Ridgmount Street[6] The library finally moved into an extension of the Bedford Way building in 1992 and was renamed the "Newsam Library" after Peter Newsam, the Director who oversaw the new construction.[6]

In 2004, the Institute of Education and Birkbeck, University of London, jointly founded London Knowledge Lab, an interdisciplinary research unit concerned with learning and technology. It is located in Emerald Street, Holborn. In 2016, by mutual and cordial agreement, the institutional collaboration came to an end with the launch of two separate research centres, the UCL Knowledge Lab and the Birkbeck Knowledge Lab, extending the legacy of the London Knowledge Lab.

Library

[edit]

The IOE's Newsam Library is the largest in its field in Europe, containing more than 300,000 volumes and nearly 2,000 periodicals.[19]

Main collections

[edit]- Educational collection of publications covering every aspect of education in the United Kingdom, organized by the specialist classification scheme, London Education Classification.[20]

- International collection covering aspects of the organisation of education outside the UK

- Reference collection including reference works, indexes, legal guidance, statistics of education in the UK and recent official government publications. The library also maintains the Digital Education Resource Archive (DERA) which contains full text digital publications from over 100 official departments and agencies relating to education, skills and training .

- Other subjects collection containing publications on educational related subjects including psychology, sociology, linguistics etc.

- Large selection of teaching materials for all subjects and stages of the curriculum with children's fiction and picture books.[21]

Special collections

[edit]There are 27 special collections of publications held by the Newsam Library. Some of the collections relate to a specific subject area or have been collection by a single source while others have been built up with several sources. The collection contains a comprehensive range of documents on education in the UK, the National Textbook Collection, and other unique resources.[22]

Archives

[edit]The institute's archive collections date back from 1797, and holds over 130 deposited collections as well as the records of the institute itself. The deposited collections contain the personal papers of educationalist and other notable people involved with education and the records of educational organisations such as trade unions, and education projects.[23] The collections cover a wide area of education, from pre-school all the way through to adult education, from formal education settings to informal settings.[24] The archives are open to both internal and external researchers by appointment only, and form part of University College London's Special Collections.[25]

Research

[edit]The IOE had a total research income of £12.17 million in 2013/14, of which £6.59 million was from UK Research Councils, £2.0 million from UK central government, £1.07 from European governments, £0.81 million from UK-based charities, and £1.7 million from other sources.[26]

A total of 219 full-time-equivalent staff from the IOE were submitted to the Education Unit of Assessment (UoA) of the 2014 Research Excellence Framework (REF), around 15 per cent of the total 1,442 staff submitted by all institutions to the UoA and by far the highest amount of any single institution (compared to 54 staff submitted by the second-placed Open University and 40 by the third-placed Edinburgh University).[27] 28% of the IOE's research was classified as 4* (compared to 19% in the 2008 Research Assessment Exercise (RAE 2008)) and 40% as 3* (compared to 38% in the 2008 RAE)[28] and the IOE achieved a GPA of 3.21, ranking it joint 11th in the UoA.[27] Furthermore, according to the UCL Institute of Education's research page, one-quarter of all UK Education research occurs at the IOE, while the IOE is home to four times as many leading education scholars than any other UK university.[29]

The IOE prepared 23 cases for impact evaluation, with the next largest submission in the UoA comprising six cases.[28] In a league table produced by Times Higher Education the IOE ranked first for "research power" in the UoA with a rating of 703 (compared to 164 for the second-placed Open University and 140 for the third-placed Oxford University).[27]

Centre for Longitudinal Studies

[edit]The Centre for Longitudinal Studies (CLS) is an ESRC Resource Centre based at the IOE. CLS houses three of Britain's internationally renowned birth cohort studies:

- National Child Development Study (NCDS)[30]

- 1970 British Cohort Study (BCS70)[31]

- Millennium Cohort Study (MCS): 2000 birth cohort

The studies were key sources of evidence for a number of UK Government inquiries such as the Plowden Committee on Primary Education (1967), the Warnock Committee on Children with Special Educational Needs (1978), the Finer Committee on One Parent Families (1966–74), the Acheson Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health (1998) and the Moser Committee on Adult Basic Skills (1997–99). A study of working mothers and early child development was influential in making the argument for increased maternity leave. Another study on the impact of assets, such as savings and investments on future life chances, played a major part in the development of assets-based welfare policy, including the much-debated "Baby Bond".

Heather Joshi was director of the Centre for Longitudinal Studies between 2003 and 2010.[32] She was succeeded by Jane Elliott, who served as director from 2010 to 2014.[33] The archives of the CLS are held within the IOE's archive collections.[34]

Notable people

[edit]Notable former faculty and staff

[edit]

- Basil Bernstein (1924–2000), sociologist and linguist

- Max Black (1909–1988), philosopher

- Cyril Burt (1883–1971), educational psychologist

- Jon Davison (1949-), first professor of teacher education

- Rosemary Firth (1912–2001), social anthropologist

- Harvey Goldstein (1939–2020), statistician

- Chris Husbands (1959–), educationalist and former director of the institute

- Susan Sutherland Isaacs, (1885–1948), educational psychologist and psychoanalyst

- George Barker Jeffery (1891–1957), mathematician and educationalist

- Joseph Lauwerys (1902–1981)

- Leonard John Lewis, international educationalist

- Karl Mannheim (1893–1947), sociologist

- Richard Stanley Peters (1919– 2011), philosopher, professor of philosophy of education

- Marion Richardson (1892–1946), artist, educator and author who published workbooks on penmanship and handwriting

- Harold Rosen (1919–2008), educationalist, professor and head of English department

- Christian Schiller (1895–1976), HM Inspector and senior lecturer

- Philip E. Vernon, (1905–1987), psychologist

Notable alumni

[edit]

- T. Q. Armar (1915–2000), Ghanaian publisher

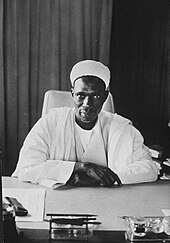

- Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa (1912–1966), first Prime Minister of independent Nigeria

- Paul Bird (1923–1993), artist and teacher

- Quentin Blake (born 1932), cartoonist, illustrator and children's book author

- Nicole Brown (social scientist) (born 1976), Austrian and British writer and academic

- Waveney Bushell, (born 1928), Guyanese-born educational psychologist

- Jane E. Clerk (1904–1999), schoolteacher and pioneer woman education administrator on the Gold Coast, now Ghana

- Reginald Horace Blyth (1898–1964), author and devotee of Japanese culture

- Valerie Davey (born 1940), former Labour Member of Parliament for Bristol West

- Bryan Davies, Baron Davies of Oldham, PC (born 1939), Labour member of the House of Lords

- Modjaben Dowuona (1908–1991), first Registrar of the University of Ghana; Minister for Education (1966–1969)

- Michael Duane (1915–1997, controversial head teacher

- U. A. Fanthorpe (1929–2009), poet

- Beryl Gilroy (née Answick) (1924–2001), novelist

- Alice Jane Green (1863 – 1966) She co-founded Moreton Bay College in Australia.

- Jonathan Gullis (born 1990), former Minister of State for School Standards

- Sally Morgan, Baroness Morgan of Huyton (born 1959), British Labour Party politician

- William R. Newland (potter) (1919–1998), New Zealand born studio potter

- Harry Mwaanga Nkumbula (1917?–1983), Zambian nationalist leader who assisted in the struggle for the independence of Northern Rhodesia

- Aydin Önaç (born c. 1950), controversial headteacher

- Harry Rée (1914–1991), British educationalist and member of the Special Operations Executive

- Bill Renwick (1929–2013), New Zealand Director-General of Education 1975–1988

- Harold Rosenthal (1917–1987), music critic

- Irene Sabatini, Zimbabwean novelist

- Brian Simon (1915–2002), educationalist and historian

- Dale Spender (1943-2023), feminist scholar

- Katherine Weare (born 1950), professor of Education

Principals and directors

[edit]Principals of the London Day Training College

- 1902–22: John Adams (1857–1934)

- 1922–32: Sir Percy Nunn (1870–1944)[6]

Directors of the Institute of Education

- 1932–36: Sir Percy Nunn (1870–1944)

- 1936–45: Sir Fred Clarke (1880–1952)

- 1945–57: George Barker Jeffery (1891–1957)

- 1958–73: Lionel Elvin (1905–2005)

- 1973–83: William Taylor

- 1983–89: Denis Lawton

- 1989–94: Sir Peter Newsam

- 1994–2000: Peter Mortimore

- 2000–11: Geoff Whitty[6]

- 2011–15: Sir Chris Husbands

- 2015–16: Andrew Brown (interim)

- 2016–2020: Becky Francis

- 2020–2021: Sue Rogers (interim)

- July 2021 – Present: Li Wei[35]

References

[edit]- ^ [1] The history of IOE, accessed on 5 April 2023

- ^ [2] About IOE, accessed on 5 April 2023

- ^ 2017 QS World University Rankings, Top Universities, accessed on 16 March 2017.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings by Subject 2014 – Education", Top Universities.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings by Subject 2016 – Education". Top Universities. QS Quacquarelli Symonds. 17 March 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Aldrich/Woodin (2021). The Institute of Education, 2e. London: UCL Press. ISBN 978-1-78735-951-2.

- ^ "London County Council Day Training College". The Times. No. 36892. London. 7 October 1902. p. 10.

- ^ Curthoys, rev. M. C. (2004). "Adams, Sir John (1857–1934)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. Online edition. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/30334. Retrieved 23 May 2008.

- ^ Institute of Education. "IE – Records of the Institute of Education". Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ "McNair Committee (Report)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Vol. 396. Parliament of the United Kingdom: House of Commons. 20 January 1944. col. 373W.

- ^ Great Britain. Board of Education. Committee to Consider the Supply, Recruitment and Training of Teachers and Youth Leaders. (1944). Teachers and youth leaders : report. H.M.S.O. OCLC 152077591.

- ^ Gillard, Derek. "Education in England: a brief history, Glossary". Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ "Bloomsbury institutions enter 'strategic partnership'". Times Higher Education. 2 October 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ "UCL set to merge with Institute of Education". Times Higher Education. 5 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ "Institute of Education will bring 'healthy dowry' to UCL marriage". Times Higher Education. 13 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ "UCL and IoE confirm merger date". Times Higher Education. 25 November 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ "UCL and IoE merger: a marriage of like minds?". Times Higher Education. 4 December 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ "New global HE research centre wins funding". Times Higher Education. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ UCL Institute of Education. "UCL Institute of Education Library". Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ^ Sakarya, Barbara. "Main Collection – Main Education Collections: UK and International – IOE LibGuides at Institute of Education, London". Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ "Archives and Special Collections". UCL Library Services. Retrieved 23 April 2009.

- ^ UCL Institute of Education (8 August 2018). "Archive & Special Collections". Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ Institute of Education. "IOE: Archive Collections". Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ^ UCL (8 August 2018). "Archives and Special Collections". Library Services. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- ^ UCL (17 May 2019). "Visiting Us". Library Services. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ "Financial Statements 2013/2014" (PDF). UCL Institute of Education. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ^ a b c "Institutions ranked by subject". Times Higher Education. 18 December 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ^ a b "UK research is getting better all the time – or is it?". The Guardian. London. 23 December 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ^ "Research". UCL Institute of Education. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ^ Power, C.; J. Elliott (2006). "Cohort profile: 1958 British Cohort Study". International Journal of Epidemiology. 35 (1): 34–41. doi:10.1093/ije/dyi183. PMID 16155052.

- ^ Elliott J and Shepherd P (2006). "Cohort profile: 1970 British Birth Cohort (BCS70)". International Journal of Epidemiology. 35 (4): 836–43. doi:10.1093/ije/dyl174. PMID 16931528.

- ^ "Professor Heather Joshi". Professors and Speakers. Gresham College. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ^ "ELLIOTT, Prof. (Barbara) Jane". Who's Who 2015. A & C Black. October 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ UCL Special Collections. "Records of the Centre for Longitudinal Studies". UCL Archives Catalogue. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

- ^ "Professor Li Wei appointed as Director and Dean of the UCL Institute of Education". UCL IOE News. 29 March 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.