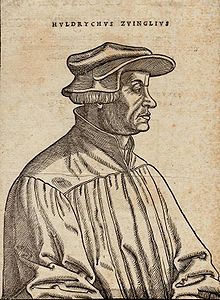

Theology of Huldrych Zwingli

The theology of Ulrich Zwingli was based on an interpretation of the Bible, taking scripture as the inspired word of God and placing its authority higher than what he saw as human sources such as the ecumenical councils and the church fathers. He also recognised the human element within the inspiration, noting the differences in the canonical gospels. Zwinglianism is the Reformed confession based on the Second Helvetic Confession promulgated by Zwingli's successor Heinrich Bullinger in the 1560s.

Zwingli's views on baptism were largely a response to Anabaptism, a movement which criticized the practice of infant baptism. He defended the baptism of children by describing it as a sign of a Christian's covenant with disciples and God just as God made a covenant with Abraham.

He denied the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation and following Cornelius Henrici Hoen, he agreed that the bread and wine of the institution signify and do not literally become the body and blood of Jesus Christ. Zwingli's differences of opinion on this with Martin Luther resulted in the failure of the Marburg Colloquy to bring unity between the two Protestant leaders.

Zwingli believed that the state governed with divine sanction. He believed that both the church and the state are placed under the sovereign rule of God. Christians were obliged to obey the government, but civil disobedience was allowed if the authorities acted against the will of God. He described a preference for an aristocracy over monarchic or democratic rule.

Scripture

[edit]The Bible is central in Zwingli's work as a reformer and is crucial in the development of his theology. Zwingli appealed to scripture constantly in his writings. This is strongly evident in his early writings such as Archeteles (1522) and The Clarity and Certainty of the Word of God (1522). He believed that man is a liar and only God is the truth. For him scripture, as God's word, brings light when there is only darkness of error.[1]

Zwingli initially appealed to scripture against Catholic opponents in order to counter their appeal to the church—which included the councils, the church fathers, the schoolmen, and the popes. To him, these authorities were based on man and liable to error. He noted that "the fathers must yield to the word of God and not the word of God to the fathers".[2] His insistence of using the word of God did not preclude him from using the councils or the church fathers in his arguments. He gave them no independent authority, but he used them to show that the views he held were not simply his own.[3]

The inspiration of scripture, the concept that God or the Holy Spirit is the author, was taken for granted by Zwingli. His view of inspiration was not mechanical and he recognized the human element in his commentaries as he noted the differences in the canonical gospels. He did not recognize the apocryphal books as canonical. Like Martin Luther, Zwingli did not regard the Revelation of St John highly, and also did not accept a "canon within the canon", but he did accept scripture as a whole.[4]

Soteriology

[edit]In the centuries leading up to the Reformation, an "Augustinian Renaissance" sparked renewed interest in the thought of Augustine of Hippo (354-430,[5] who is widely regarded as the most influential patristic figure of the Reformation.[6] Zwingli rooted his theology of salvation deeply in Augustinian soteriology[7] alongside Martin Luther (1483-1546)[8] and John Calvin (1509–1564).[9] Augustine's theology was grounded in divine monergism,[10] and implied a double predestination.[11] Similarly, Zwingli's vision centered also on divine monergism.[12] He affirmed that God predetermined both election to salvation and reprobation.[13]

Baptism

[edit]Zwingli's views on baptism are largely rooted in his conflict with the Anabaptists, a group whose beliefs included the rejection of infant baptism in favor of believer's baptism and centered on the leadership of Conrad Grebel and Felix Manz. In October 1523, the controversy over the issue broke out during the second Zürich disputation and Zwingli vigorously defended the need for infant baptism and his belief that rebaptism was unnecessary. His major works on the subject include Baptism, Rebaptism, and Infant Baptism (1525), A Reply to Hubmaier (1525), A Refutation (1527), and Questions Concerning the Sacrament of Baptism (1530).[14]

In Baptism, Rebaptism, and Infant Baptism, Zwingli outlined his disagreements with both the Catholic and the Anabaptist positions. He accused the Anabaptists of adding to the word of God and noted that there is no law forbidding infant baptism. He challenged Catholics by denying that the water of baptism can have the power to wash away sin. Zwingli understood baptism to be a pledge or a promise, but he disputed the Anabaptist position that it is a pledge to live without sin, noting that such a pledge brings back the hypocrisy of legalism. He argued against their view that those that received the Spirit and were able to live without sin were the only persons qualified to partake in baptism. At the same time he asserted that rebaptism had no support in scripture. The Anabaptists raised the objection that Christ did not baptise children, and so Christians, likewise, should not baptise their children. Zwingli responded by noting that kind of argument would imply women should not participate in communion because there were no women at the last supper. Although there was no commandment to baptise children specifically, the need for baptism was clearly stated in scripture. In a separate discussion on original sin, Zwingli denies original guilt. He refers to I Corinthians 7:12–14 which states that the children of one Christian parent are holy and thus they are counted among the sons of God. Infants should be baptised because there is only one church and one baptism, not a partial church and partial baptism.[15]

The first part of the document, A Reply to Hubmaier, is an attack on Balthasar Hubmaier's position on baptism. The second part where Zwingli defends his own views demonstrates further development in his doctrine of baptism. Rather than baptism being simply a pledge, he describes baptism as a sign of our covenant with God. Furthermore, he associates this covenant with the covenant that God made with Abraham. As circumcision was the sign of God's covenant with Abraham, baptism was the sign of his covenant with Christians.[16] In A Refutation, he states,

The children of Christians are no less sons of God than the parents, just as in the Old Testament. Hence, since they are sons of God, who will forbid this baptism? Circumcision among the ancients ... was the same as baptism with us.[17]

His later writings show no change in his fundamental positions. Other elements in Zwingli's theology would lead him to deny that baptism is a means of grace or that it is necessary for salvation. His defence of infant baptism was not only a matter of church politics, but was clearly related to the whole of his theology and his profound sense of unity of the church.[18]

Eucharist

[edit]The Eucharist was a key center of controversy in the Reformation as it not only focused differences between the reformers and the church but also between themselves. For Zwingli it was a matter of attacking a doctrine that imperiled the understanding and reception of God's gift of salvation, while for Luther it was a matter of defending a doctrine that embodied that gift. It is not known what Zwingli's eucharistic theology was before he became a reformer and there is disagreement among scholars about his views during his first few years as a priest. In the eighteenth article of The Sixty-seven Articles (1523) which concerns the sacrifice of the mass, he states that it is a memorial of the sacrifice. He expounds on this in An Exposition of the Articles (1523).[19]

Zwingli credited the Dutch humanist, Cornelius Henrici Hoen (Honius), for first suggesting the "is" in the institution words "This is my body" meant "signifies".[20] Hoen sent a letter to Zwingli in 1524 with this interpretation along with biblical examples to support it. It is impossible to say how the letter affected Zwingli's theology although Zwingli claimed that he already held the symbolic view when he read the letter. He first mentioned the "signifies" interpretation in a letter to Matthäus Alber, an associate of Luther. Zwingli denies transubstantiation using John 6:63, "It is the Spirit who gives life, the flesh is of no avail", as support.[21] He commended Andreas Karlstadt's understanding of the significance of faith, but rejected Karlstadt's view that the word "this" refers to Christ's body rather than the bread. Using other biblical passages and patristic sources, he defended the "signifies" interpretation. In The Eucharist (1525), following the introduction of his communion liturgy, he laid out the details of his theology where he argues against the view that the bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ and that they are eaten bodily.[22]

The conflict between Zwingli and Luther began in 1525, but it was not until 1527 that Zwingli engaged directly with Luther. The culmination of the controversy was the Marburg Colloquy in 1529.[23] He wrote four responses leading up to the meeting: A Friendly Exegesis (1527), A Friendly Answer (1527), Zwingli's Christian Reply (1527), and Two Replies to Luther's Book (1528). They examined Luther's point-of-view rather than systematically presenting Zwingli's own. Some of his comments were sharp and critical, although they were never as harsh and dismissive as some of Luther's on him. However, Zwingli also called Luther "one of the first champions of the Gospel", a David against Goliath, a Hercules who slew the Roman boar.[24] Martin Bucer and Johannes Oecolampadius most likely influenced Zwingli as they were concerned with reconciliation of the eucharistic views.[25]

The main issue for Zwingli is that Luther puts "the chief point of salvation in the bodily eating of the body of Christ". Luther saw the action as strengthening faith and remitting sins. This, however, conflicted with Zwingli's view of faith. The bodily presence of Christ could not produce faith as faith is from God, for those whom God has chosen. Zwingli also appealed to several passages of scripture with John 6:63 in particular. He saw Luther's view as denying Christ's humanity and asserted that Christ's body is only at one place and that is at the right hand of God.[26] The Marburg Colloquy did not produce anything new in the debate between the two reformers. Neither changed his position, but it did produce some further developments in Zwingli's views. For example, he noted that the bread was not mere bread and affirmed terms such as "presence", "true", and "sacramental". However, it was Zwingli's and Luther's differences in their understanding of faith, their Christology, their approach and use of scripture that ultimately made any agreement impossible.[27]

Near the end of his life Zwingli summarized his understanding of the Eucharist in a confession sent to King Francis I, saying:[28]

"We believe that Christ is truly present in the Lord’s Supper; yea, we believe that there is no communion without the presence of Christ. This is the proof: 'Where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them' (Matt. 18:20). How much more is he present where the whole congregation is assembled to his honor! But that his body is literally eaten is far from the truth and the nature of faith. It is contrary to the truth, because he himself says: 'I am no more in the world' (John 17:11), and 'The flesh profiteth nothing' (John 6:63), that is to eat, as the Jews then believed and the Papists still believe. It is contrary to the nature of faith (I mean the holy and true faith), because faith embraces love, fear of God, and reverence, which abhor such carnal and gross eating, as much as any one would shrink from eating his beloved son.… We believe that the true body of Christ is eaten in the communion in a sacramental and spiritual manner by the religious, believing, and pious heart (as also St. Chrysostom taught). And this is in brief the substance of what we maintain in this controversy, and what not we, but the truth itself teaches."[28]

State

[edit]

For him, the church and state are one under the sovereign rule of God. The development of the complex relationship between church and state in Zwingli's view can only be understood by examining the context of his life, the city of Zürich, and the wider Swiss Confederation. His earliest writings before he became a reformer, such as The Ox (1510) and The Labyrinth (1516), reveal a patriotic love of his land, a longing for liberty, and opposition to the mercenary service where young Swiss citizens were sent to fight in foreign wars for the financial benefit of the state government. His life as a parish priest and an army chaplain helped to develop his concern for morality and justice. He saw his ministry not limited to a private sphere, but to the people as a whole.[29]

The Zürich council played an essential role at each stage of the Reformation. Even before the Reformation, the council operated relatively independently on church matters although the areas of doctrine and worship were left to the authority of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. As Zwingli was convinced that doctrinal matters had to conform to the word of God rather than the hierarchy, he recognised the role of the council as the only body with power to act if the religious authorities refused to undertake reform. His theocratic views are best expressed in Divine and Human Righteousness (1523) and An Exposition of the Articles (1523) in that both preacher and prince were servants under the rule of God. The context surrounding these two publications was a period of considerable tension. Zwingli was banned by the Swiss Diet from travelling into any other canton. The work of the Reformation was endangered by the potential outbreak of religious and social disorder. Zwingli saw the need to present the government in a positive light to safeguard the continued preaching of the Gospel. He stated,

The relationship between preacher and magistrate was demonstrated by two forms of righteousness, human and divine. Human righteousness (or the "outward man") was the domain of the magistrate or government. Government could secure human righteousness, but it could not make man righteous before God. That was the domain of the preacher where the "inward man" is called to account for divine righteousness.[30][31]

As government was ordained by God, Christians were obliged to obey in Zwingli's view. This requirement applied equally to a good or an evil government because both came from God. However, it is because rulers are to be servants of God and that Christians obey the rulers as they are to obey God, that the situation could arise when Christians may disobey. When the authorities act against the will of God then Zwingli noted, "We must obey God rather than men." God's commands took precedence over man's.[32]

In his Commentary on Isaiah (1529), Zwingli noted that there were three kinds of governments: monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy. He expressed his preference for aristocracy which is not surprising given his experience with the Zürich council. In the publication, rather than comparing the three forms of government, he gave a defence of aristocracy against a monarchy. He argued that a monarchy would invariably descend to tyranny. A monarchy had inherent weaknesses in that a good ruler could be easily replaced by a bad one or a single ruler could be easily corrupted. An aristocracy with more people involved did not have these disadvantages.[33]

See also

[edit]- Calvinism

- Lutheranism

- Theology of Anabaptism

- Swiss Reformed Church

- Consensus Tigurinus

- Helvetic Consensus

- Affair of the Sausages

Notes and references

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Stephens 1986, p. 51

- ^ Huldreich Zwinglis Samtliche Werke, Vol. III, 505–509, as quoted in Stephens 1986, p. 52

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 52–53

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 55–56

- ^ George 1988, p. 49.

- ^ Pelikan 1987.

- ^ Stephens 1986, p. 153.

- ^ George 1988, p. 48.

- ^ McMahon 2012, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Barrett 2013, p. xxvii, . "[D]ivine monergism is the view of Augustine and the Augustinians."

- ^ James 1998, p. 103. "If one asks, whether double predestination is a logical implication or development of Augustine's doctrine, the answer must be in the affirmative."

- ^ Akin, Dockery & Finn 2023, Ch. History of the Doctrine of Providence. "Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin fully embraced the monergism incipient in Augustine."

- ^ James 1998b. "Zwingli attributes both to the divine will in the same way, constructing an absolutely symmetrical doctrine of double predestination. The cause and means of both election and reprobation are precisely the same. For Zwingli, God is the exclusive and immediate cause of all things."

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 194–199

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 199–206

- ^ Courvoisier 1963, pp. 66–67

- ^ Huldreich Zwinglis Samtliche Werke, Vol. VI i 48.10–15, as quoted in Stephens 1986, pp. 209–210

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 206–216

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 218–219

- ^ Potter 1976, pp. 292–293. For more information, see Spruyt, Bart Jan (2006), Cornelius Henrici Hoen (Honius) and His Epistle on the Eucharist (1525), Leiden: E.J. Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-15464-3.

- ^ Courvoisier 1963, pp. 67–69

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 227–235

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 235–236

- ^ Huldreich Zwinglis Samtliche Werke, Vol. V, 613.12–13, 722.3–5, 723.1–2, as quoted in Stephens 1986, p. 242

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 241–242

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 242–248

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 248–250

- ^ a b Schaff, P. (1878). The Creeds of Christendom, with a History and Critical Notes: The History of Creeds (Vol. 1, p. 375). New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers.

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 282–285

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 286–298

- ^ Courvoisier 1963, pp. 81–82. Courvoisier uses the word justice rather than righteousness for Gerechtigkeit in the original German.

- ^ Courvoisier 1963, pp. 84–85; Stephens 1986, pp. 302–303

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 308–309

Sources

[edit]- Akin, Daniel L.; Dockery, David S.; Finn, Nathan A. (2023). A Handbook of Theology. Brentwood, TN: B&H Publishing Group.

- Barrett, Matthew (2013). Salvation by Grace: The Case for Effectual Calling and Regeneration. Phillipsburg: P & R Publishing.

- Courvoisier, Jaques (1963), Zwingli, A Reformed Theologian, Richmond, Virginia: John Knox Press

- George, T. (1988). Theology of the Reformers. Nashville: Broadman Press.

- James, Frank A. (1998). Peter Martyr Vermigli and Predestination: The Augustinian Inheritance of an Italian Reformer. Oxford: Clarendon.

- James, Frank A. (1998b). "Neglected Sources of the Reformation Doctrine of Predestination Ulrich Zwingli and Peter Martyr Vermigli". Modern Reformation. 7 (6): 18–22.

- McMahon, C. Matthew (2012). Augustine's Calvinism: The Doctrines of Grace in Augustine's Writings. Coconut Creek, FL: Puritan Publications.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav (1987). "An Augustinian Dilemma: Augustine's Doctrine of Grace versus Augustine's Doctrine of the Church?". Augustinian Studies. 18: 1–28. doi:10.5840/augstudies1987186.

- Potter, G. R. (1976), Zwingli, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-20939-0

- Stephens, W. P. (1986), The Theology of Huldrych Zwingli, Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 0-19-826677-4

- Zwingli, Huldrych, Huldreich Zwinglis Sämtliche Werke Vols. I-XIV (in German), Zürich: Theologisher Verlag

Further reading

[edit]- Blackburn, William M. (1868), Ulrich Zwingli, the Patriotic Reformer: A History, Philadelphia: Presby. Board of Publications

- Christoffel, Raget (1858), Zwingli: or, The Rise of the Reformation in Switzerland, Edinburgh: T & T Clark

- Grob, Jean (1883), The Life of Ulric Zwingli, New York: Funk & Wagnalls

- Hottinger, Johann Jacob (1856), The Life and Times of Ulric Zwingli, Harrisburg: T.F. Scheffer.*Jackson, Samuel M. (1900), Huldreich Zwingli, the Reformer of German Switzerland, 1484–1531, New York: G.P. Putnam's

- Locher, Gottfried W. (1981), Zwingli's Thought: New Perspectives, Leiden: E.J. Brill

- Simpson, Samuel (1902), Life of Ulrich Zwingli, the Swiss Patriot and Reformer, New York: Baker and Taylor

Older German / Latin editions of Zwingli's works available online include:

- Huldreich Zwinglis sämtliche Werke, vol. 1, Corpus Reformatorum vol. 88, ed. Emil Egli. Berlin: Schwetschke, 1905.

- Analecta Reformatoria: Dokumente und Abhandlungen zur Geschichte Zwinglis und seiner Zeit, vol. 1, ed. Emil Egli. Zürich: Züricher and Furrer, 1899.

- Huldreich Zwingli's Werke, ed. Melchior Schuler and Johannes Schulthess, 1824ff.: vol. I; vol. II;vol. III; vol. IV; vol. V; vol. VI, 1; vol. VI, 2; vol. VII; vol. XIII.

- Der evangelische Glaube nach den Hauptschriften der Reformatoren, vol. II: Zwingli, ed. Paul Wernle. Tübingen: Mohr, 1918.

- Von Freiheit der Speisen, eine Reformationsschrift, 1522, ed. Otto Walther. Halle: Niemeyer, 1900.

See also the following English translations of selected works by Zwingli:

- The Latin Works and the Correspondence of Huldreich Zwingli, Together with Selections from his German Works.

- Vol. 1, 1510–1522, New York: G.P. Putnam and Sons, 1912.

- Vol. 2, Philadelphia: Heidelberg Press, 1922.

- Vol. 3, Philadelphia: Heidelberg Press, 1929.

- Selected Works of Huldreich Zwingli (1484–1531). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1901.

- The Christian Education of Youth. Collegeville: Thompson Bros., 1899.

External links

[edit]- (in German) Zwingliana (since 1897, since 1993 annually), Zürich, ISSN 0254-4407.