Smith of Wootton Major

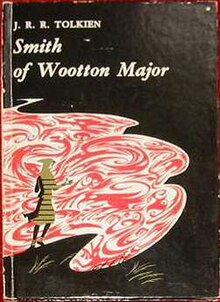

First edition front cover; the illustration extends over the spine to the back cover. | |

| Author | J. R. R. Tolkien |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Pauline Baynes |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Fantasy novella |

| Publisher | George Allen & Unwin |

Publication date | 9 November 1967[1] |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 224 |

| Preceded by | The Road Goes Ever On |

| Followed by | Bilbo's Last Song (posthumous) |

Smith of Wootton Major, first published in 1967, is a novella by J. R. R. Tolkien. It tells the tale of a Great Cake, baked for the once in twenty-four year Feast of Good Children. The Master Cook, Nokes, hides some trinkets in the cake for the children to find; one is a star he found in an old spice box. A boy, Smith, swallows the star. On his tenth birthday the star appears on his forehead, and he starts to roam the Land of Faery. After twenty-four years the Feast comes around again, and Smith surrenders the star to Alf, the new Master Cook. Alf bakes the star into a new Great Cake for another child to find.

Scholars have differed on whether the story is an allegory or is, less tightly, capable of various allegorical interpretations; and if so, what those interpretations might be. Suggestions have included autobiographical allusions such as to Tolkien's profession of philology, and religious interpretations such as that Alf is a figure of Christ. The American scholar Verlyn Flieger sees it instead as a story of Faërie in its own right.

This was Tolkien’s last major work published before his death in 1973.

Background

[edit]J. R. R. Tolkien was a scholar of English literature, a philologist and medievalist interested in language and poetry from the Middle Ages, especially that of Anglo-Saxon England and Northern Europe.[T 1][2]

Smith of Wootton Major began as an attempt to explain the meaning of Faery by means of a story about a cook and his cake, and Tolkien originally thought to call it The Great Cake.[3] It was intended to be part of a preface by Tolkien to George MacDonald's fairy story The Golden Key.[3]

Plot summary

[edit]The village of Wootton Major was well known around the countryside for its annual festivals, which were particularly famous for their culinary delights. The biggest festival of all was the Feast of Good Children. This festival was celebrated only once every twenty-four years: twenty-four children of the village were invited to a party, and the highlight of the party was the Great Cake, a career milestone by which Master Cooks were judged. In the year the story begins, the Master Cook was Nokes, who had landed the position more or less by default; he delegated much of the creative work to his apprentice Alf. Nokes crowned his Great Cake with a little doll jokingly representing the Queen of Faery. Various trinkets were hidden in the cake for the children to find; one of these was a star the Cook discovered in the old spice box.

The star was not found at the Feast, but was swallowed by a blacksmith's son. The boy did not feel its magical properties at once, but on the morning of his tenth birthday the star fixed itself on his forehead, and became his passport to Faery. The boy grew up to be a blacksmith like his father, but in his free time he roamed the Land of Faery. The star on his forehead protected him from many of the dangers threatening mortals in that land, and the Folk of Faery called him "Starbrow". The book describes his many travels in Faery, until at last he meets the true Queen of Faery. The identity of the King is also revealed.

The time came for another Feast of Good Children. Smith had possessed his gift for most of his life, and the time had come to pass it on to some other child. So he regretfully surrendered the star to Alf, and with it his adventures into Faery. Alf, who had become Master Cook long before, baked it into the festive cake once again for another child to find. After the feast, Alf retired and left the village; and Smith returned to his forge to teach his craft to his now-grown son.

Publication history

[edit]

The story was first published in the United Kingdom as a stand-alone book by George Allen & Unwin on 9 November 1967, with 11 black and white illustrations and a coloured jacket illustration by Pauline Baynes.[T 2] Tolkien had asked Baynes to limit her palette to black and white, as she had done for Farmer Giles of Ham; he was pleased with the result.[4]

Smith of Wootton Major was first published in the United States by Houghton Mifflin the same year.[T 3] It was reprinted in 1969 by Ballantine together with Farmer Giles of Ham.[T 4]

The 2005 edition, edited by Verlyn Flieger, includes a previously unpublished essay by Tolkien, explaining the background and just why the elf-king spent so long in Wootton Major. It also explains how the story grew from this first idea into the published version.[T 2]

The story was republished in 2021 together with Farmer Giles of Ham, The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, and "Leaf by Niggle" as Tales from the Perilous Realm.[T 5]

Analysis

[edit]Allegory

[edit]The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey writes that "defeat hangs heavy" in the story,[6] while Tolkien called it "an old man's book", with presage of bereavement.[T 6] Shippey adds that when Tolkien presents images of himself in his writings, as with Niggle, the anti-hero of "Leaf by Niggle" and Smith, there is "a persistent streak of alienation".[7] While Tolkien had stated that the story was "not 'allegory'", he had immediately added "though it is capable of course of allegorical interpretation at certain points".[8] Shippey presents evidence in support of the claim.[8]

| Story element | Allegorical meaning | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Nokes | Unsympathetic literary critic (as opposed to philologists like Tolkien) | Noke, Oxfordshire, from Middle English *atten okes (at the oaks); Nokes's family all with nunnated names, Nell, Nan, Ned for Ell[en], Ann, Ed[ward]; Tolkien had arranged teaching at the University of Leeds into an A-scheme (literature) and a B-scheme (philology); for Tolkien, A meant Old English ac (oak), B meant beorc (birch) |

| Nokes's Great Cake | Literary study, offering "not much food for the imagination" | "no bigger than was needed ... nothing left over" |

| "Old books of recipes left behind by previous cooks" | Old philology | |

| Old Cook | Philologist | |

| The fay-star | "Vision, receptiveness to fantasy, mythopoeic power" | |

| Smith | Tolkien himself | Smith "never bakes a Great Cake"; Tolkien "never produced a major full-length work on medieval literature" |

| Alf | Elf, reassuring guide to Faërie | Old English ælf (elf); Alf is eventually revealed as King of Faërie |

| Wootton Major | The "wood of the world" where people wander "bewildered" | Old English wudu-tún ("town in the wood") |

Capable of allegorical interpretation

[edit]

Josh B. Long, in Tolkien Studies, states that for Tolkien, "allegorical interpretation" was not the same as allegory, as interpretations come from a free interchange between text and reader, whereas allegory is imposed by the author. Long sees both religious "undertones" in the story, and autobiographical elements. He notes that the Catholic writer Joseph Pearce took the story as a parable,[9][10] and that Flieger accepts "a level of allegory" but not the philological version proposed by Shippey.[9][11] Instead, the Hall would be the church, Cook would be the parson, and cooking would be "personal religion".[9] Or, Matthew Dickerson and Jonathan Evans suggest, Alf is a figure of Christ, the king of a heavenly realm who arrives as a child and grows to be a man.[9] Martin Sternberg sees the story as religious, with experiences of the numinous and "traditional mystical ideas and motifs".[9]

Long presents his own religious interpretation, likening the story's Faery Queen to the Virgin Mary, with the lilies "near the lawn" as her symbol; Alf as Christ; the Great Cake perhaps as a Twelfth-cake for Epiphany; Nokes as a fool or "a kind of anti-Tolkien"; Smith, a "lay Christian".[9]

In addition, Long sees Shippey's identification of birch and oak with philology and criticism as correct, but differs about what Tolkien wanted to say here. In Long's view, the birch "represents the sharp critique of most of his philological colleagues who supposed that Tolkien had squandered years of his life on a worthless piece of fantasy literature—a place he didn’t belong, or so they thought." In other words, he writes, the dispute was inside the philological community; far from fighting literary criticism, Tolkien had done much to heal the split between the critics and the philologists at Oxford.[9]

Visit to Faërie

[edit]Flieger opposes viewing Smith of Wootton Major as an allegory, instead seeking comparisons with Tolkien's other fantasies.[8][12] She argues that the story had sufficient "bounce" that no allegorical explanation was necessary, and indeed that such explanation detracts from the story of travels in the land of "Faery" and the element of mystery.[12] She likens the "first Cook" to a whole series of "Tolkien's far-traveled characters", namely Alboin Errol, Edwin Lowdham, Frodo Baggins, Eärendil, Ælfwine-Eriol "and of course Tolkien himself—all the Elf-friends."[11]

Further, Flieger sees "thematic connections" between the story and the "dark power and ... echoes of a past too deep to forget" of his poem "The Sea-Bell" (1962, with a history going back to his 1934 "Looney"). The two works share a distinctive feature: a "prohibition against the return to Faërie."[11] She states, however, that the two works describe the prohibition in differing moods and at different times. "The Sea-Bell" was written at the beginning of Tolkien's career, "cry[ing] for lost beauty"; Smith of Wootton Major almost at its end, "an autumnal acceptance of things as they are".[11] She comments, too, that "The Sea-Bell" could be a "corrective" reply to J. M. Barrie's 1920 play Mary Rose; and that Smith of Wootton Major could then be a reply, much later, to his own poem.[11] Whether or not that was the intention, she writes, Tolkien sought to "create a true fairy-tale quality without the use of a traditional fairy-tale plot."[11]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Baynes presented the original illustration of Smith and his family to the Tolkien scholars Wayne G. Hammond & Christina Scull for their engagement.[5]

References

[edit]Primary

[edit]- ^ Carpenter 2023, #131 to Milton Waldman, late 1951

- ^ a b Tolkien, J. R. R.; Flieger, Verlyn (2005). Smith of Wootton Major. HarperCollins. p. Jacket. ISBN 978-0-00-720247-8.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1967). Smith of Wootton Major. Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 849891109.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1969). Smith of Wootton Major: and Farmer Giles of Ham. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-3453-3606-4. OCLC 2949056.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (2021). Tales from the Perilous Realm. Mariner Books. ISBN 978-0-3586-5296-0.

- ^ Carpenter 2023, Letter 299 to Roger Lancelyn Green, 12 December 1967

Secondary

[edit]- ^ Scull, Christina; Hammond, Wayne G. (2006). The J. R. R. Tolkien Companion and Guide. Vol. Chronology. HarperCollins. p. 711. ISBN 978-0-618-39113-4.

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 146–149.

- ^ a b Carpenter 1977, p. 244 "Headington".

- ^ a b Hasirci, Baris (2021). "An Examination of Fantasy Illustration and the Illustrations of Pauline Baynes and John Howe Through the Writings of J. R. R. Tolkien" (PDF). Journal of Social Research and Behavioral Sciences. 7 (14): 44. doi:10.52096/jsrbs.7.14.3. ISSN 2149-178X.

- ^ Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (9 September 2012). "Our Collections: Pauline Baynes". Too Many Books and Never Enough. Archived from the original on 2 June 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ Shippey 2005, p. 315 "On the Cold Hill's Side".

- ^ Shippey, Tom (2004). "Tolkien and the Appeal of the Pagan: Edda and Kalevala". In Chance, Jane (ed.). Tolkien and the Invention of Myth: A Reader. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 163–178. ISBN 0-8131-2301-1.

- ^ a b c d Shippey 2005, pp. 309–319 "On the Cold Hill's Side".

- ^ a b c d e f g h Long, Josh B. (2021). "Faery, Faith, and Self-Portrayal: An Allegorical Interpretation of Smith of Wootton Major". Tolkien Studies. 18: 93–129. doi:10.1353/tks.2021.0007.

- ^ Pearce, Joseph (1998). Tolkien: Man and Myth. Ignatius Press. p. 170.

- ^ a b c d e f Flieger, Verlyn (2001). "Pitfalls in Faërie". A Question of Time: J.R.R. Tolkien's Road to Faërie. Kent State University Press. pp. 227–253. ISBN 0-87338-699-X.

- ^ a b Flieger, Verlyn; Shippey, Tom (2001). "Allegory Versus Bounce: Tolkien's 'Smith of Wootton Major'". Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 12 (2 (46)): 186–200. JSTOR 43308514.

Sources

[edit]- Carpenter, Humphrey (1977). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-04-928037-3.

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (2023) [1981]. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien: Revised and Expanded Edition. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-35-865298-4.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth: How J. R. R. Tolkien Created a New Mythology (Third ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-261-10275-0.

External links

[edit]- Introduction and overview of Smith of Wootton Major at Tolkien-online.com